October 29, 2012

On our last full day in Uzbekistan we boarded an Uzbekistan Airways flight back to Nukus. Our flying companions were mainly composed of oil and gas engineers searching for black gold in the area around Nukus.

Once we arrived in Nukus we began the long drive to Muynak, a former port on the Aral Sea. I say “former” because the Aral Sea has retreated some 100 miles from Muynak, leaving a vast desert in place of the sea once plied by the pride of the Soviet fishing fleet. As the sea receded, Muynak’s once prosperous industrial fishing and canning industry collapsed and thousands of residents fled the city in search of better lives. The remaining residents suffer from a multitude of illnesses brought about by the toxic laden dust carried by powerful windstorms sweeping across the dried up seabed.

But how did this happen? As part of the Soviet Union’s “Great Plan for the Transformation of Nature”, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers that fed the Aral Sea would be re-purposed for irrigation. Instead of flowing to the Aral Sea, as they had for thousands of years, the majority of the river water would be diverted to the desert to grow cotton, with just a trickle of water making its way to the Aral Sea. The Soviet plan succeeded, much to the detriment of the sea and people of Muynak, and now Uzbekistan is the world’s 6th largest producer of cotton. The Aral Sea was sacrificed for the “white gold” that has become a mainstay of the Uzbek economy.

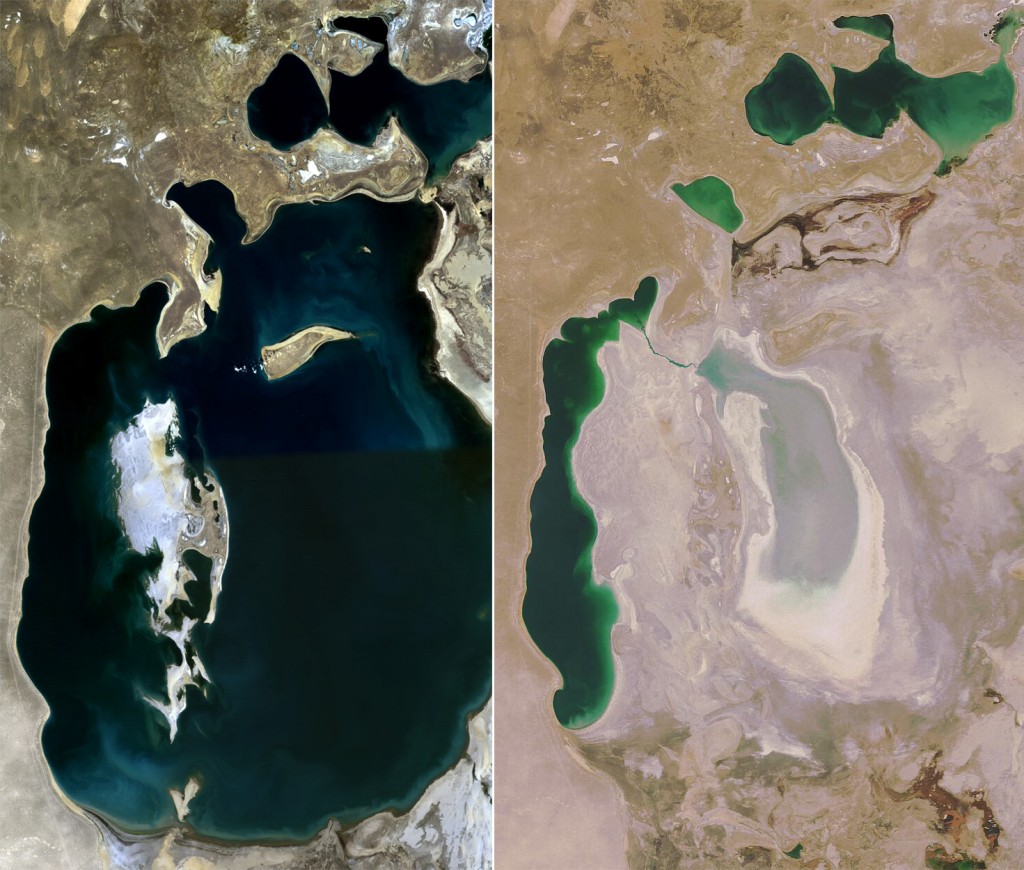

But they say a picture is worth a thousand words:

Comparison of the Aral Sea, 1989 vs 2008 via NASA satellite

We arrived in Muynak after a four hour drive from Nukus. The city is very run down, as one might expect after the local economy has been obliterated due to the decision of central planners in Moscow. There is a chance that nearby oil & gas exploration will be successful, but it is doubtful that any of the wealth from those projects would benefit the citizens of Muynak.

We visited the ship graveyard, a collection of old fishing boats stranded in the dunes that now make up the former seabed. It was hard to believe that there was once a sea here; the surrounding landscape reminded me of the desert I grew up in.

This monument marks the former shore of the Aral Sea

Small museum with exhibits about Muynak’s heyday as a fishing port

Our visit to Muynak was short, and we reached Nukus by dinnertime after the long drive back. Our dinner was rather sedate until a raucous birthday party erupted in the main room of the restaurant. Curious, a few of us left our table to check it out and soon found ourselves on the dance floor with a group of friendly Uzbeks, dancing our asses off to Lady Gaga and “Gangnam Style”. Compared to my new Uzbek friends, who were decked out in their finest, I felt quite grungy in my hiking pants and sand filled shoes. Still, we were warmly welcomed and it remains one of my fondest memories of the trip. It was the perfect way to say goodbye to Uzbekistan.